Artikel: Mode ist wenn man trotzdem Lacht

Mode ist wenn man trotzdem Lacht

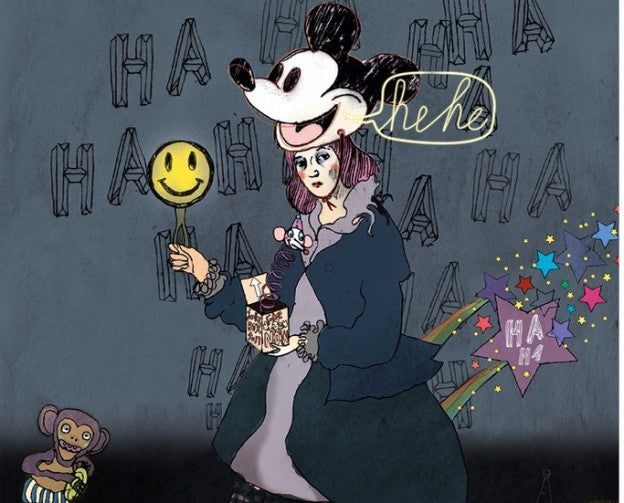

Fredericke Winklers neuester Artikel für das J`N`C Magazin. Illustration von Frauke Berg.

Wenn wir eines mit unserem Aufzug nicht erreichen wollen, dann, dass andere über uns lachen. Mode darf alles sein; provokativ, skandalös, skurril, fremd, ja selbst unzumutbar. Nur witzig darf sie nicht sein. Fröhliche Kleider sind ja so provinziell. Wird ein Outfit als lustig bezeichnet, ist dies eine nette Umschreibung für ‚nicht gekonnt‘. Wenn Mode zum Schmunzeln anregt, hat sie ihre besten Zeiten längst hinter sich. Dabei – so sagen Psychologen und Mediziner – lässt uns der Humor nicht nur zufriedener und smarter, sondern auch schöner durch die Welt gehen. Warum also nimmt sich die Mode so furchtbar ernst? Oder verstehen wir ihre Späße nur nicht?

Neulich übernahm ich das ehrenvolle Amt, als Teil einer Jury Arbeiten von Modestudierenden zu bewerten. Manche waren gut, andere weniger. Besonders in Erinnerung geblieben ist mir jedoch eine Kollektion, die an gedankenloser Hässlichkeit kaum zu überbieten war. Ohnehin schon minderwertige Stoffe wurden mit der Nähmaschine zu textilen Gebilden zusammengefügt, die mir weder tragbar noch sinnhaft erschienen. Und während ich mich darum bemühte, meine Gesichtszüge unter Kontrolle zu bringen, lauschte ich der tiefernsten Schwurbelei über den geistigen Überbau der Arbeit, von dem der Student äußerst eloquent zu erzählen wusste. Diese Situation war mit Abstand die komischste, die ich seit Langem erlebt habe. Und zwar, weil das Gesagte und das Gesehene so weit auseinandergingen.

„Humor ist das umgekehrt Erhabene. Er erniedrigt das Große, um ihm das Kleine, und erhöht das Kleine, um ihm das Große an die Seite zu setzen“, so das Plädoyer des Schriftstellers Jean Paul, die Dinge mit mehr Heiterkeit anzugehen. Erscheint uns ein Übel zu groß, setzen wir neue Maßstäbe à la ‚es könnte noch schlimmer sein‘, und schon relativiert sich nahezu alles. Auch wenn die besagte Präsentation ein klassisches Beispiel für ungewollte Komik ist: Die im besten Wortsinn absurde Idee, die offensichtlich dilettantische Kollektion auf eine Stufe mit echter Qualitätsarbeit zu stellen, hat mich dennoch fasziniert. Warum? Weil sie die Erhabenheit der Mode grundsätzlich zur Disposition stellt.

Mich erinnerte die Situation an einen Sketch von Hape Kerkeling für seine Sendung ‚Total Normal‘. Darin verkörperte Kerkeling einen polnischen Opernsänger, der ein experimentelles Musikstück vortrug, welches mit einem lauten „Hurz“ endete. Die besondere Würze dieser gelungenen Parodie auf die (pseudo-)intellektuelle Kunstszene: Das Publikum lauschte der Darbietung mit wohlwollender Anerkennung. Hätte mein Studierender seine Präsentation mit einem lauten „Hurz“ beendet, wäre die Arbeit sicher mit der Bestnote bewertet worden. Allerdings nicht als Modekollektion, sondern als künstlerisches Werk, dessen Verdienst darin bestanden hätte, die allzu übertriebene Ernsthaftigkeit der Branche zu persiflieren. Denn Mode muss vorrangig den Körper schmücken und darf ihn – aus welchem Grund auch immer – nicht verunglimpfen.

Heiter bis modisch

Als Handlangerin der vorherrschenden Schönheitsideale darf Mode ihre Erhabenheit nicht riskieren. Denn sie funktioniert durch den menschlich angeborenen Drang zur Nachahmung des ‚Besseren‘. Zu dem Schluss gelangt jedenfalls, wer sich Immanuel Kants ‚Anthropologische Bemerkungen über den Geschmack‘ zur Brust nimmt, und auch eine Lektüre von Georg Simmels ‚Über die Mode‘ legt eine derartige Interpretation nahe. Roman Meinhold bezeichnet dieses Streben nach Verbesserung in ‚Der Mode-Mythos: Lifestyle als Lebenskunst‘ als einen Akt der „Melioration“ verbunden mit dem Ziel der ästhetischen Wertsteigerung des menschlichen Körpers. Mithilfe von Kleidung kann sich der Mensch optimieren und genießt dadurch soziale Anerkennung. Damit Mode also ihren Sinn erfüllt, muss sie ihrem Träger die Möglichkeit geben, sich gemäß dem Verständnis seines Umfelds aufzuhübschen. Komik jedoch basiert auf dem Regelbruch, auf einer aktiven Distanzierung von Erwartungen und sozialen Annahmen. Eine komische Person will sich nicht verbessern, sie will kontrapunktieren. Sie verweist mithilfe von Sprache oder anderen Ausdrucksmitteln auf das, was sie diskutabel findet. Sie hat Spaß an der Sinnlosigkeit und findet in ihr neuen Sinn. Sie führt Dinge zusammen, die auf den ersten Blick keinerlei Verbindung haben, und spürt in diesen abstrusen Gebilden kleine Wahrheiten auf. Laut Duden ist Humor eine Haltung von „heiterer Gelassenheit“. Gelassenheit gegenüber den Widrigkeiten des Lebens.

Kurz: Humor zeigt auf das Unperfekte in der Welt und er hilft dem Humorvollen, damit fröhlich umzugehen. Mode indes strebt stets der Perfektion zu. Ihre Aufgabe besteht darin, Makel zu verhüllen, um die Aufmerksamkeit auf die körperlichen Vorzüge zu lenken. Bei dieser konträren Bestimmung: Wie bitte sollen diese beiden Darstellungsprinzipien zueinanderfinden?

Life is too short for size zero

Zunächst müssen wir unterscheiden zwischen dem Subjekt, das etwas komisch findet, und dem Gegenstand oder der Person, die komisch erscheint. Mode muss also erst einmal nicht offensichtlich Humor haben, damit wir sie in einem gewissen Kontext amüsant finden. Im Gegenteil zeigt die Erfahrung, dass vor allem Bierernstes danach schreit, auf die Schippe genommen zu werden. Wer also ist schuld, wenn der Mode der Jux fehlt? Der Träger natürlich. Denn Mode erfüllte durchaus auch weiter ihre Bestimmung der Optimierung, wenn man sie hier und da auf ihr ironisches Potenzial abgeklopft und den guten Joke dann auch bringt.

„Nun, aller höhere Humor fängt damit an, dass man die eigene Person nicht mehr ernst nimmt.“ Diesen Satz legte schon Hermann Hesse seinem Pablo in ‚Der Steppenwolf‘ in den Mund. Bevor man über andere herzlich lachen kann, muss man also erst einmal lernen, sich über sich selbst lustig zu machen. Die Krux mit der Selbstironie? Sie fällt einem Steppenwolf beziehungsweise einer sogenannten Randgruppe leichter als Personen, die für sich eine reelle Chance sehen, auf der Welle des Mainstreams mitzureiten. Frauen mit überdurchschnittlicher Körperfülle setzen ihre Option auf Melioration keineswegs dadurch aufs Spiel, dass sie ein T-Shirt mit dem Print ‚Life is too short for size zero!‘ tragen. Im Gegenteil. Sie verabschieden weithin sichtbar allgemeine Schönheitsideale und machen sich in puncto Kleidergröße unangreifbar, nicht ohne den dezenten Hinweis, in anderer Hinsicht glänzen zu können. Damit bleiben sie zwar dem Prinzip der Mode verhaftet, welche immer ein Zusammenspiel von Verhüllung hier und Zurschaustellung dort ist. Allerdings fehlt zum Modischen die Massenkompatibilität. Denn erstens braucht es die entsprechenden Rundungen, damit das Shirt überhaupt Sinn macht. Zweitens muss man seine Botschaft lustig finden, um es zu erwerben, und drittens den Mut haben, es zu tragen. Die Gruppe derer, auf die alle drei Kriterien zutreffen, ist schlicht zu klein, um ein modisches Phänomen zu begründen.

Textiler Spaß kann also nur dann entstehen, wenn eine Gruppe von Menschen einen gemeinsamen Stil und ähnlichen Sinn für Humor teilt und sich zudem jemand findet, der daraus eine Kollektion strickt. Stimmt der Wiedererkennungswert, kann es gelingen, sich genussvoll im Kollektiv von realen wie vermeintlichen Defiziten zu distanzieren. Wenn das ökofaire Label bleed ein T-Shirt mit dem Aufdruck ‚I can dance my name‘ auf den Markt bringt, dann macht es sich über das Klischee der vom alternativen Lebensstil ihrer Eltern geprägten Öko-Aktivisten der neueren Generation lustig (Stichwort: Eurythmie-Unterricht in der Waldorfschule). Das T-Shirt ist beim Junglabel der Renner, was zum einen nahelegt, dass an dem Klischee tatsächlich einiges dran sein könnte, zum anderen auf die Fähigkeit dieses Milieus verweist, über sich selbst zu lachen.

„Insofern die Mode ‚Schlechtere‘ nachzuahmen sucht, wird sie zur Komödie. Dies kommt sicher nicht oft vor, trifft aber beispielsweise bei Fasnachtskostümierung zu, wenn die Verkleidung als Räuber, Prostituierte, Clown oder Penner gewählt wird. Dabei ist jedoch die Frage zu stellen, ob die genannten Vorbilder aus einer bestimmten Perspektive des jeweils Verkleideten nicht doch als ‚besser‘ erscheinen, warum sonst hätte diese sich gerade so verkleidet? Denn innerhalb des jeweiligen sozialen Kontextes und innerhalb der ‚Rationalität‘ des darauf bezogenen individuellen Kalküls erscheint der ‚Schlechtere‘ dennoch als ‚Bessere‘“, beschreibt Meinhold das Phänomen der modischen Selbstverhöhnung.

Perfekt unperfekt

Gehört das Unperfekte zum ästhetischen Leitbild einer Personengruppe, und der humorvolle Umgang mit ihm zur Kommunikationskultur, muss die Mode sogar einen ironischen Unterton haben. Sie muss die Perfektion im Unperfekten finden, damit man sich mit ihr optimal schmücken kann. Dies wäre zumindest eine fantastische Erklärung für den Erfolg von Brands wie Comme des Garçons, Jean Paul Gaultier oder Gareth Pugh. Sie sind bekannt für die Übertreibung und die Deformierung der körperlichen Silhouette. Ein Stilmittel mit dessen Hilfe sie die allgemein anerkannten Konventionsformen von Schönheit infrage stellen. Womöglich aus einem anderen Grund erinnern die Ergebnisse oft an Narrenkostüme, wenn auch ohne die clowneske Unbeholfenheit. Und wer weiß; vielleicht hat sich Hedi Slimane beim Entwurf der neuen Yves-Saint- … Entschuldigung: Saint-Laurent-Kollektion vor Lachen in die Hosen gemacht. Denn mit Ihr hat er – und wenn man Pierre Bergé glauben darf – ganz bewusst für schlechte Kritiken vonseiten der Presse gesorgt mit dem sicheren Wissen, bei den Einkäufern zu punkten. Er sollte recht behalten, denn der regelrechte Neustart des Traditionsunternehmen ist enorm erfolgreich, was die krakeelenden Kritiker irgendwie als humorlose Stümper dastehen lässt, nicht? Und wie genau ist Emma Hills wunderschöne, aber dennoch etwas zottelige Kollektion für Mulberry vom zurückliegenden Herbst/Winter zu verstehen, die nach Auskunft der Designerin vom Kinderbuchklassiker ‚Wo die wilden Kerle wohnen‘ inspiriert wurde?

Um ästhetisch anerkannt zu werden, muss eine Kollektion keineswegs alle Regeln befolgen. Sie muss nicht zugleich körperlichen Schönheitsidealen, saisonalen Farbschemata und Komfortansprüchen entsprechen. Warum also den Freiraum nicht mal nutzen, um einen guten Witz zu erzählen? Glaubt man dem Designer Franco Moschino, der bis zu seinem frühen Tod 1994 als großer Ironiker der High Fashion galt, gilt es dabei eigentlich nur eine Regel zu befolgen: „Lustige Mode muss extrem gut gemacht sein, weil sie dann den nötigen Chic hat. Es ist einfach, mit einem bedruckten T-Shirt lustig zu sein, aber es ist umso cleverer, dafür einen Nerzmantel zu verwenden. Schließlich wäre selbst Kaviar nicht so interessant, wenn er weniger kosten würde.“ (Vgl.UK Vogue vom August 2009)

Spricht Franco Moschino von ,gut gemacht‘, spielt er damit allerdings nicht nur auf die Qualität der Verarbeitung und des Materials an, sondern auch auf das Design. Denn selbst, wenn in ihr der Schalk steckt, muss Mode ihren Zweck erfüllen. Sie darf also weder albern rüberkommen, noch sarkastisch, sondern muss dem Träger zugewandt sein und sein Bedürfnis nach Melioration charmant zu befriedigen wissen. Andernfalls käme es zur Distanzierung der Mode vom Träger. Mode ist aber ein Schmarotzer. Verliert sie den direkten Kontakt zu ihrem Wirt, geht sie ein wie eine Primel. Ein Problem, dem das High-Fashion-Label Prada in dem Kurzfilm ‚A Therapy‘ offensiv begegnet. Der vierminütige Spot (Regie: Roman Polanski!) erzählt von einer Upperclass-Lady (Helena Bonham Carter in voller Prada-Montur), die zu ihrem Therapeuten (Ben Kingsley) kommt, sich dort aufs Sofa fläzt und ohne links und rechts zu schauen zu erzählen beginnt. So bekommt sie nicht mit, dass ihr Therapeut mehr und mehr von ihrem Prada-Pelzmantel auf dem Garderobenständer abgelenkt wird. Am Ende kann er nicht mehr an sich halten und schlüpft selbst in den Mantel – ein ekstatischer Augenblick, der trocken mit dem Ausspruch kommentiert wird: ‚Prada suits everyone‘. Der Film sprüht vor charmanter Selbstironie, bleibt aber in jedem Moment ‚pradaesk‘ edel und überzeugte damit nicht nur die Kunden der Modemarke, sondern auch das Publikum des Cannes Filmfestivals.

Karl Lagerfeld gelingt die leichtfüßige Distanzierung von den eigenen Schwächen, indem er sich regelmäßig selbst auf den Arm nimmt. „Ich kann mich, Gott sei Dank, (…) über mich selbst lustig machen. Was mich natürlich nicht daran hindert, mich auch über andere lustig zu machen“, erklärte er dem ‚Stern‘ im Dezember 2006 (Nr. 51). Spätestens seit seinem letzten Auftritt bei ‚Wetten, dass …?‘ im Oktober 2012 ist er für sein Talent zur Selbstparodie aus dem Stehgreif bekannt und beliebt. Dort hat er auf die Frage, ob er sich gut findet geantwortet: „Nicht, dass ich mich gut finde… Aber es könnte schlimmer sein.“ Fast scheint es, als hätte Karl Lagerfeld Sigmund Freuds Werk ‚Der Humor‘ von 1927 durchgeackert, wo es bezüglich Sinn und Zweck spöttischen Verhaltens heißt: „Das Großartige liegt offenbar im Triumph des Narzissmus, in der siegreich behaupteten Unverletzlichkeit des Ichs. Das Ich verweigert es, sich durch die Veranlassungen aus der Realität kränken, zum Leiden nötigen zu lassen, es beharrt dabei, dass ihm die Traumen der Außenwelt nicht nahegehen können, ja es zeigt, dass sie ihm nur Anlässe zu Lustgewinn sind. Dieser letzte Zug ist für den Humor durchaus wesentlich.“ Im Falle Karl Lagerfeld überträgt sich die Unverletzlichkeit des Ich und der Lustgewinn offenbar auch auf jene, über die sich der King so genüsslich lustig zu machen beliebt. Denn trotz seiner staubtrockenden Gehässigkeit lacht jeder gerne über seine Scherze, selbst die Verhöhnten. In einem Interview mit der B.Z. 28.Mail 2013 wunderte er sich über das Wohlwollen der Öffentlichkeit, obwohl er doch eher bekannt für seine „kritischen Worte“ sei. Er empfinde das als eine Art Narrenfreiheit, alles sagen zu können und dennoch gemocht zu werden. Womöglich wird er eher gerade deswegen gemocht, und vor allem weil er sich selbst dabei nicht ausschließt. Im Jahr 1905 hatte sich Freud bereits eingehend mit dem Witz beschäftigt. ‚Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewussten‘ so der Titel des Werks, in dem Freud diese Technik zum Lustgewinn und zur Vermeidung von Konflikten erstmals genauer unter die Lupe nimmt. Mit dem Witz überwinden wir Hemmungen, verabschieden uns von Scham und Anstand und können uns für kurze Momente dem grenzenlosen, aber dennoch sozial akzeptierten Genuss hingeben. Wir bauen Spannungen ab und solidarisieren unserem Gegenüber, das unseren Spaß versteht und Lustgewinn teilt.

Mit anderen Worten: Humor schafft Nähe zu Gleichgesinnten und schützt vor Angriffen auf die Persönlichkeit durch Außenstehende. Wäre das nicht auch eine fantastische Definition für Mode? In diesem Sinne gratuliere ich den mutigen Kreateuren, die sich bei aller Ernsthaftigkeit im Umgang mit dem Thema für ein ironisches Augenzwinkern nicht zu schade sind. Einen besonderen Gruß an alle Modemarken, die ihre Fans darin bestärken, das Leben mit heiterer Gelassenheit zu nehmen. Allen anderen empfehle ich an dieser Stelle einmal laut „Hurz“ zu rufen. Denn wenn wir eines mit unserem Aufzug nicht erreichen wollen, dann, dass andere über uns lachen. Also tun wir es doch lieber selbst.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar

Diese Website ist durch hCaptcha geschützt und es gelten die allgemeinen Geschäftsbedingungen und Datenschutzbestimmungen von hCaptcha.